RETURN

This story is the second part of Pádraig’s life that began with «The Village Elder.» It is based on the life of my father, Paddy Ahumada Gallardo, but it is not his biography, which is much broader and more interesting than what you will see in this story. I hope you like it.

Dedicated to all those people who, despite feeling fear, take action and change the world.

Ghosts.

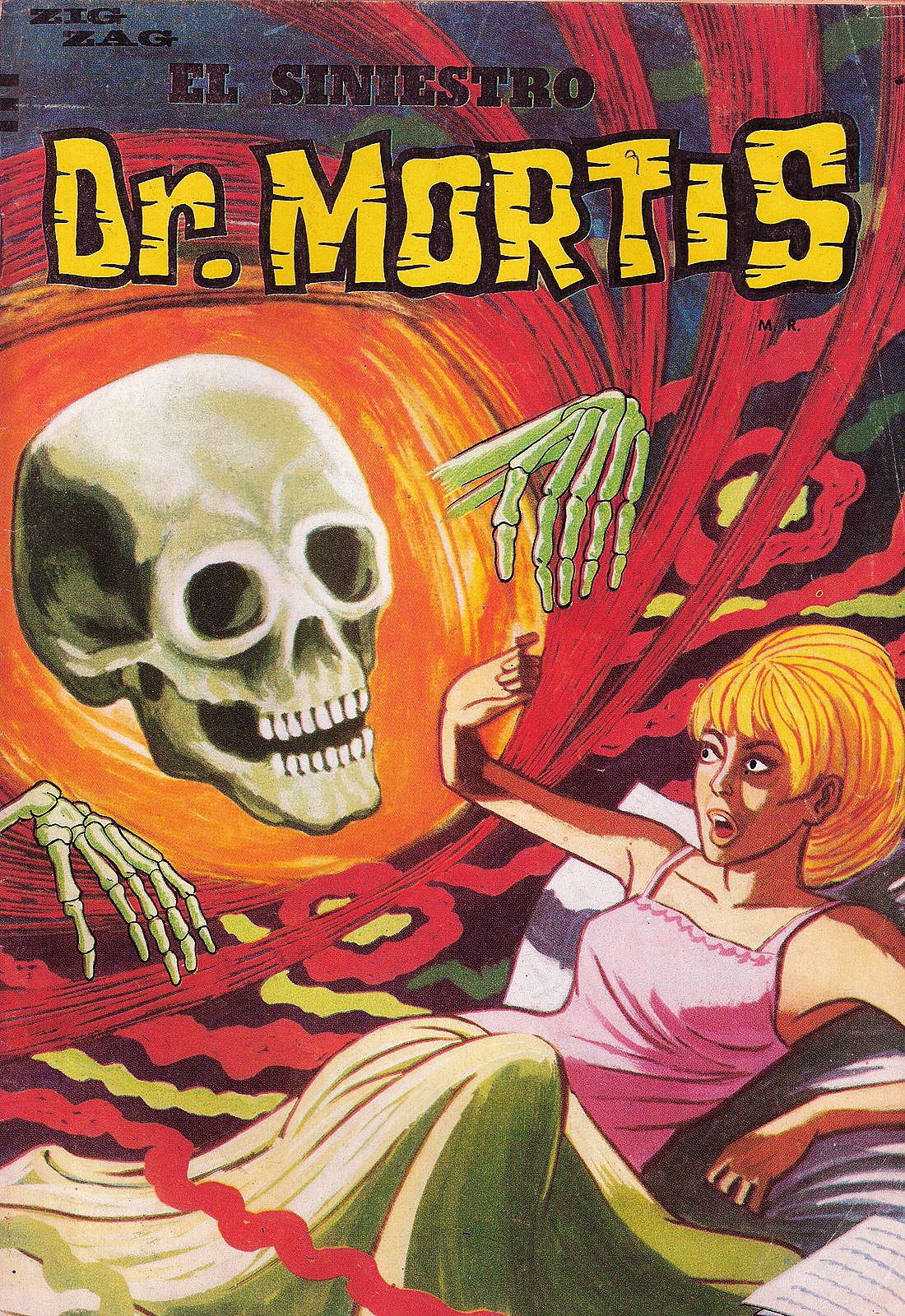

For several nights, she had been waking up frightened. She was certain she heard noises and footsteps in her room, but when she opened her eyes, there was no one there. Elena, nine years of age, constantly regretted reading the magazine ‘The Sinister Doctor Mortis,’ lent to her by a neighbor’s daughter who was two years older and apparently could read horror comics without suffering from endless nightmares. Since then, she would wake up at night, hearing strange noises in the house.

On a Saturday morning, her mother asked why she was so tired and Elena told her everything. Her mother advised her to stop reading such nonsense that upset her; those magazines were for adults. The matter would have rested there, had it not been for the fact that just then, her father entered the kitchen and her mother relayed the incident. Elena was sure her father would echo her mother’s words and perhaps scold her a bit. However, Elena’s heart leapt when she saw her father’s face turn to real fear. It was the same fear he had shown when he found out his brother had been hit by a car and was in the hospital.

The Sinister Doctor Mortis

Dad, are there really ghosts in our house?’ Elena asked her father, overwhelmed with worry. Her father looked at her, took a deep breath, and assured her that there were no ghosts. Ghosts did not exist.

‘But I hear them at night,’ Elena persisted.

‘Those are just the sounds of the house cooling down. You know houses creak at night,’ her father explained.

‘Please, Dad, I’m not that young. They sound like footsteps and noises as if someone is moving furniture. The house doesn’t sound like that.’

‘Look, since tomorrow is Sunday, you can stay up reading tonight. If you hear any strange noises, let me know, and I’ll spend a good while in your room with you. But no reading those nonsensical Doctor Mortis stories.’

‘Yes! Thank you, Dad,’ Elena replied and gave her father a hug.

There was no need for her father to come. Elena stayed up late reading the latest Mampato and didn’t hear any strange noises. She fell asleep without realizing it and slept soundly until the next day.

Monsters do exist, but not all are monstrous.

Pádraig was startled by a noise in the room. It was Saturday afternoon, and the house was supposed to be empty since the whole family had gone out. He turned and saw the trapdoor in the floor opening, revealing Miguel, the homeowner.

«Is something wrong? I thought you had gone to see your mother,» Pádraig inquired.

Miguel sat on the bed, as there was only one chair in the small attic, and said somewhat awkwardly, «Sorry, comrade, but I had to come back to ask you to make less noise. My daughter, who sleeps just below, hears you at night. Thankfully, she thinks it’s a ghost and hasn’t realized there’s someone here.»

«My apologies, comrade, and don’t worry. I’ll try not to move much. I appreciate you hiding me in your house and am very aware of the danger you’re in by doing so. But… it would help if you could bring me another book, because I’ve read Asimov too many times.»

«It would be my pleasure, comrade, and sorry for the inconvenience. I know this is very hard, but we can’t risk anyone knowing you’re here. Not even my wife knows how dangerous this all is. I haven’t told her.»

After Miguel left, Pádraig took the opportunity to walk around. He was almost always bent over due to the ceiling height, but he needed to exercise. Then he took the mattress and placed it on the floor. The bed frame made too much noise when he moved, and he couldn’t risk the girl hearing him. He dismantled the frame and put it in a corner before sitting in the chair to continue reading «Second Foundation,» the third part of Asimov’s trilogy.

At night, when he heard the children shouting goodnight, he carefully lay down on the floor and thought about his situation. In the attic of a house in Valparaíso, not seeing a soul, making no noise, and putting an entire family in danger. The process of persecution, torture, and death methodically followed by the Chilean military instilled terror in some people who crumbled and were capable of anything to avoid harm, but in others, like Miguel and his wife, it created a sense of community and union with all left-wing people persecuted by the dictatorship. That’s why they had opened their doors, and he was here.

I closed my eyes and remembered when they took me from the Chacabuco saltpeter office, which the dictatorship had turned into a concentration camp, to the Valparaíso prison. It was a regular prison with common criminals who turned out to be much more humane and approachable than any police or military personnel. Without the political prisoners realizing it, they had formed a protective circle around us so that the internal problems of the prison wouldn’t affect us. One day, I saw a group of them taking someone to a cell and beating him up. When I asked why they were doing that to an older man who was watching, he told me that this man had snitched to the guards, leading to the raid on my cell. Indeed, a week earlier, the guards had dismantled my cell looking for something. They only found an old Marx book that a comrade’s family had managed to get in, and he had passed it on to me.

«But if nothing really happened in the end, should they beat him like that?» I asked.

«Don’t worry about this. It’s our business. That guy is a snitch, and we don’t accept that,» he replied, ending the conversation. Later, I was told that the older man was a sort of leader among the common prisoners and had taken us under his protection. I imagined that he or someone close to him was left-wing, but the truth is that neither I nor anyone else knew why he had protected us.

A few weeks later, it became official that I was there, and my wife found out and requested a visit. Since she had been released from Lebu, she had been searching for me, but no one would tell her where I was. She arrived with my two daughters and son, whom I often thought I would never see again, but there they were, smiling yet with distressed faces. My wife updated me on the situation of many people, including many dead friends, and I began to realize the terrible scale of everything that was happening. But all of this did not take away the joy of seeing my wife and children for a while.

More than a month had passed since my family’s visit when I learned that I would be taken for interrogation and judgment by a military judge. They took me out of the prison, handcuffed at the feet and hands, and put me in an open-top navy van. Throughout the journey down from Loma de Elías to the center, absolutely no one looked at me. Not even when we stopped at a traffic light and people passed a few meters from me. Fear already controlled people’s lives. We arrived at the naval courts in Plaza Prat in the center of Valparaíso and entered one of the rooms. The interrogation and subsequent sentence would be carried out by the Naval Prosecutor of the Navy’s Command. I expected nothing good until I saw that the person on the stand was Álvaro Santamaría, a former student of the Patmos School. He looked at me and his face immediately changed to one of anger. «Damn,» I thought, but what he said was:

«Immediately remove the chains from the prisoner!»

The guards, taken aback, quickly removed my chains and stood at attention, looking at their superior officer who watched them with an angry gaze.

«Step back and approach, Mr. Pádraig,» he ordered.

I approached, altering my stance to one of self-assured body language.

«And what are you doing here, Álvaro?» I said, using the voice and tone of a teacher. I knew that when a student encounters a former teacher, they inadvertently adopt a student-teacher attitude. With this in mind, I treated him as a student and not as the prosecutor who held my life in his hands.

«Please sit down, Mr. Pádraig. Forgive the way the guards have treated you.»

«Don’t worry, Álvaro.»

«Well, Pádraig. Why are you here?»

«Well, Álvaro, you know better than I do. Because I’ve done nothing. Absolutely nothing. I was a CORFO official, in workers’ education. I wasn’t involved in anything.» I said in a close but formal tone that I used in class with my students. The truth was that I had held positions of responsibility in the Socialist Party, so obviously I had done things, including training groups of young Socialists in the use of explosives, something I learned from my father while working together in the mine where I spent some years. But the prosecutor knew nothing of this.

«Indeed, Mr. Pádraig, I have been looking at your file and there is nothing unusual. Let me tell you something. I was assigned your case, and when I saw your name, I went to my superior and explained to Admiral that I had been your student, you being my teacher in mathematics and physics. So I respectfully requested to be relieved from this case and for another prosecutor to be assigned. The only response I got was ‘You simply do your duty. Dismissed.’ That’s what I have done by studying your file, and I have decided to release you.»

I couldn’t believe it. Could it really be this easy? Álvaro kept his word, and three days later I was released.

Clandestine

Upon my release, I discovered job offers in Mexico and Venezuela, but I chose to stay in Chile. Years later, looking back, I realized that was the moment when I lost everything because I decided to join the underground struggle. I worked with Exequiel Ponce in Santiago, gradually taking on more responsibilities and eventually becoming the Secretary-General of Organization, responsible for the finances. I thought we could achieve something since we had the hope of the historical memory of the Chileans, but we still had no idea of the extent and number of assassinations the armed forces were carrying out. Today, it would be called genocide.

The Armed Forces were loyal to the constitution, according to Allende. But in the Socialist Party (PS), we didn’t believe that, although the Communist Party (PC) did. In long conversations with Carlos Altamirano, already in exile, I realized that many in the PS thought the armed forces were traitors, who would sooner or later try to hinder the process. But at that time in Chile, we had very little information about the extent of the repression and thought that what we were doing would be useful.

There came a point when, with all the information I had, I became someone who could not fall into the hands of the Armed Forces. So, it was decided that I had to hide, and overnight I disappeared from public view, taking refuge in the home of Miguel and his family.

Lying there on that mattress, I decided that I had to leave that house as soon as possible. If they were caught, Miguel’s entire family would be shattered, just like mine had been. I knew almost nothing about them. The last news I had received was that they had managed to cross the border and were in Argentina. I knew nothing more but hoped they were safe.

Miguel was a mathematics teacher at a vocational training institute, and one of his students was Marcelo, my contact with the outside world. He came once a week, officially for extra lessons with Miguel on the day Juana, the children’s mother, worked late and the kids were at music lessons at the conservatory. When he came, I told him about the girl’s ghost and that I couldn’t stay there much longer without endangering the whole family. He agreed with me.

A few weeks later, on a day when the house was empty, precisely at five, a white Peugeot 204 van was waiting for me at the door. I immediately recognized the driver. It was Azucena, my sister.

«What the hell are you doing here?!» I asked angrily.

«Stop looking at me like that and get in the car. Don’t attract anyone’s attention.» She was obviously right, so I complied and sat beside her.

«Do you realize how dangerous what you’re doing is?» I asked, trying to control my fear and anger.

«I know, but your comrades are being captured everywhere, and your contact suspects a mole. Since I’ve never been involved in anything and lead a quiet life, I was the perfect, and I suspect the only, candidate,» she replied.

«Please, don’t ever do something like this again. One idealistic revolutionary in the family is enough.»

She looked at me with the same expression she used when one of her students said something silly but only said, «What’s the matter? Don’t you trust your little sister?»

«It’s not about that…»

«I know, but you’re my brother and I can help. Now, check the bag in the back for some meat empanadas mom made and eat something. You’re very thin.»

We crossed Valparaíso during rush hour and headed towards Viña del Mar, then took the road to Quillota. We didn’t stop talking, and although I occasionally asked about party comrades, she didn’t know any. However, she updated me on how our mother, my children, and also my ex-wife were doing. We had separated a few months after I got out of prison. She was now with the kids in Argentina, a country that would soon experience a military coup, and the Argentine junta would agree with Chile’s to persecute left-wing Chileans, make them disappear, or send them back to Chile to an uncertain future. They called it Operation Condor. But at that moment, as my sister drove me out of Valparaíso, none of that had happened yet, and I enjoyed the conversation as I never thought I could with simple chatter. Then, a doubt crossed my mind.

«Where are we going?»

«We’re heading to Putaendo. There’s a retired friend living there who will take you in. Don’t you have a bag or suitcase?» she asked.

I looked at her, smiling. «There’s no time for such things. I’m wearing what I’ve got, a toothbrush, two pairs of socks, and two pairs of underwear in my jacket pockets.»

«With the toothbrush? I hope the underwear is clean.»

Our laughter was instant.

Heroes

Maria was the name of my sister’s friend, identical to that of our mother. She dwelt near the end of the main thoroughfare, in a quaint semi-detached dwelling crafted from burgundy adobe, with brown doors and windows, meticulously maintained. Maria had retired from her role as a mathematics teacher in Rancagua, but had returned to the abode bequeathed by her parents. She also received a pension from her late husband, who had passed merely weeks after the military coup.

«He died of a broken heart,» she confided in me one day. He was a former communist militant, who had battled throughout his life for the downtrodden of Chile to have a glimmer of hope, a vision he saw mirrored in Allende’s governance. But the betrayal of the armed forces was too much for him, and one morning he simply didn’t awaken.

«It is in his memory that you are now here,» Maria said to me. «I’ve never meddled in politics, but I couldn’t allow the military to catch you. It’s what my husband would have done.»

My chamber was at the rear of the house, accessed through an internal courtyard. Spacious, with two windows overlooking the yard and antique, yet well-kept furniture. The mattress was new and everything spotless. It reminded me of my youth in our family home in Rancagua. Although I couldn’t approach the windows facing the street, I was free to roam the house and yard and converse with Maria. Yet, an unexpected delight was discovering the books of Juan Carlos, Maria’s husband. They ranged from car mechanics and astronomy to science fiction and Marx – a veritable treasure trove.

One morning, Maria handed me an envelope. A mysterious woman had given it to her.

«She approached me as if she knew me. Offered condolences for Juan Carlos and suggested we should meet more often. As we parted, she leaned in for a kiss and whispered that she had left an envelope in my shopping bag for you. She said her name was Ida.»

Ida was my partner at the time, and if she had taken such a risk, it meant something significant had happened. I took a deep breath and opened the envelope.

They had caught Marcelo and tortured him to death. They kept asking one question: «Where is Pádraig?» Marcelo knew my location, and clearly, he hadn’t divulged it, or else I’d be the one undergoing torture. His silence saved my life and possibly those of many in the resistance, of whom I knew many, as I managed their finances. I don’t know who remembers him, nor his real name; Marcelo was his nom de guerre. Even now, many years later, whenever I experience a truly beautiful moment, like a breathtaking sunset, a good book, a surprise visit from a loved one, or when my partner Carmen smiles at me with a look full of love, I think, “Thank you, Marcelo. Thank you.”

Spy network

When Ida was finally able to visit me, I learned that, having been in hiding for so long, my name no longer surfaced in the torture sessions of my comrades. Hence, the urgency of my pursuit and capture was diminishing. She stayed with me for two days before returning to her routine, cautious not to arouse suspicion that might alert DINA, the secret police. After a little more than a month in that tranquil haven, it was decided that with the situation somewhat calmer, I should relocate. A week later, on Monday at eight in the morning, I was to exit the house and board a car waiting for me.

The day before my departure, I expressed my gratitude to Maria. At the appointed hour, I opened the door just as a car arrived. The sight of the white Peugeot 204 didn’t surprise me. I got in, and Azucena immediately started the car.

«Your knack for being a resistance agent is quite remarkable,» I said, foregoing greetings. Seeing her involved in such perilous undertakings again unsettled me.

«I know, it’s dangerous… blah, blah, blah. But I’ll repeat, you’re my brother, and I’ll do everything to keep you safe. Even mum agrees.»

«But mum’s not in danger,» I retorted.

«That’s because you don’t know where we’re going.»

«What do you mean?»

«We’re heading to our home in Rancagua. Mum will be delighted to see you.»

«What! That’s absurd! It’s the first place they’ll look.»

«Ida told us they’re not asking about you in the interrogations anymore. And we haven’t seen DINA’s henchmen lurking near our home for weeks now. Don’t worry. You’ll be safe.»

«You shouldn’t be so certain. They might just be hiding better.»

«Mrs. Elsa from the fruit shop, whose youngest son, a MIR member, disappeared, knows everyone in the neighbourhood. She assures me there haven’t been any suspicious people on the corners for weeks. And Juan, a former unionist in Sewell, now retired, walks the streets at different hours. A month ago, I asked him about DINA’s presence, and he said there was no trace of them. Two other neighbours, whom Juan identified as leftists, visit me for tea and update me if they’ve seen any secret police. As you see, I’ve got my own network of elderly spies. I can assure you there’s no secret police in the neighbourhood anymore.»

«This is far riskier than you realise. You shouldn’t involve strangers.»

«Look, these people have family and friends who’ve disappeared or been killed. They don’t know why I want to know about the secret police’s presence, but just by informing me, they feel useful. They feel they’re contributing their bit in the struggle against these treacherous soldiers.»

Caught in the Monday morning traffic between San Felipe and Santiago, Pádraig felt immense pride for his sister. He knew she was made of extraordinary mettle, which only surfaced on rare occasions. With people like her and her network of elderly spies, he was certain that, as President Allende said before his death, «one day free men would walk once again the grand boulevards». He only hoped to witness it.

Rancagua

Arriving at the old family home instilled in me an odd sense of security. Of course, I knew it was an illusion; should the DINA discover my presence, those ancient adobe walls would hardly stall them. Yet, I felt ensconced in safety.

Maria, my mother, whose health had seen better days, seemed to find a new lease on life with the need to look after me. She took upon herself all the household duties, a relief to my sister, who could then depart for her mathematics teaching job at the Liceo de Niñas in Rancagua with a lighter heart.

Initially, my mother and I engaged in endless conversations, but soon enough, we settled back into our routine. My sister decreed visits to be a biweekly affair, fearing the neighbours might notice an unusual flurry of guests. Particularly since my mother was not in the habit of hosting acquaintances at home. Ida kept me informed not only about the fate of our comrades but also about my children’s wellbeing in Argentina. My ex-wife was navigating the bureaucratic maze to secure refugee status for herself and the children, hoping to escape, for with Videla’s coup, Argentina had turned into a perilous haven for Chilean leftists.

Though the search for me had cooled, one day, Ida, my partner, came with the urgent news that I must leave Chile at once. My knowledge, albeit no longer a priority for the hunters, was still a treasure trove that must never fall into the dictatorship’s hands. A month later, a person from the Finnish embassy arrived one morning to escort me away. Tearful goodbyes were exchanged with my sister and mother, the uncertainty of our next meeting hanging heavily in the air.

«Be strong,» my mother said. «It won’t be long before we see each other again.»

The Finn, who held a diplomatic post, drove me in his personal car to his residence. The following morning, he took me to the Civil Registry for an emergency passport that would allow me to leave but not return. He revealed that the entire operation had cost a hundred thousand dollars, paid by the German Democratic Republic to the Minister of the Interior. More precisely, into General Benavides’s pockets, ensuring my name would be omitted from customs controls for six hours, allowing me to catch a Lufthansa flight to Germany. Who could have guessed that the same corruption leading those generals to betray their country to American interests would be my ticket to safety?

The plane was scheduled for one in the afternoon, and I had to be at the airport by eleven sharp, for it was between ten in the morning and two in the afternoon that my name would vanish from customs, police, and military records. To my astonishment, the plane was empty, save for myself. The captain, approaching me with a heavy German accent but speaking in English, assured me, «Mr. Ahumada, you are now on German soil. Here, no one can touch you.» Yet, well aware of the Chilean military’s scant regard for laws and rules, I found no solace until we touched down in Peru, our first stop before continuing on to New York. There, our company grew to twelve as we were joined by two families with their children, all of us confined to a windowless room with two doors until our onward journey to Hamburg commenced.

On the flight, after eating the meal they provided, I went to the loo and on my way, I crossed paths with the two fathers who were chatting. As I passed by, one asked me, «Excuse me for asking, but are you also being expelled from the country?»

«Yes,» I responded, «I was a socialist leader.»

«Comrade! What a relief. We thought you were some DINA sod coming to spy on us.»

It turned out they were peasant leaders from San Fernando, home to powerful peasant federations. Both were communists but had never flown before. They shared a problem: they and their kids were terribly hungry. They had no money and each time they were offered food, they thought it had to be paid for. With so many children, they assumed they couldn’t afford it, so they had been declining it. Their joy was immense when I told them that the food on these flights was free. I explained their situation in English to a flight attendant who, with a smile, said she would bring them food immediately. A grand feast for all at more than ten thousand feet above the Atlantic.

They stayed in Hamburg where they were received as heroes by friends and authorities. I continued on to Denmark where, four hours later, I had a flight to East Germany, as there were no direct flights between the two Germanies. But upon landing in Denmark, an old friend was waiting for me. With only a small handbag, I went with him to his house. I spent a week there, enjoying chats, food, and wine until the East Germans found me, and only because my friend took me to the East German embassy. Quite a commotion ensued when I showed up since they had been searching for me all that time without my knowledge. The East Germans quickly organised themselves and I had to continue my journey to East Germany. Later, I learned that the East German security officer in Denmark had been reprimanded for not noticing that I had left the airport and had been missing for a week, having a bloody good time, but they didn’t care about that.

German Democratic Republic

In Germany, they sent me south, near the Polish border, for five months in a sort of political quarantine. To the German security services, I was an enigma, potentially a leftist refugee or a spy for the United States. One day, Altamirano, the leading figure of the Socialist Party in exile, visited me. Recognised by the GDR government as a trustworthy individual, his endorsement finally gained me acceptance. I was then sent to Berlin to join my partner, who had also managed to escape Chile. In Berlin, the Socialist Party appointed me as the Executive Secretary of the Central Committee in Exile. This position seemed significant to the Germans, being second only to Altamirano, so they provided me with a decent flat in Berlin and considerable freedom of movement. I was given a special passport that allowed me to cross into West Berlin for minor shopping trips – fruits, chocolates, or drinks. It was a pleasant time after all the turmoil in Chile, but Berlin revealed the falsehoods of history, always written and manipulated by the victors.

One of the first things that struck me while walking around the city was that despite the intense bombing of Berlin during the Second World War, the Detlev-Rohwedder Haus, then the Ministry of Aviation, had survived perfectly intact. What was it about that building that allowed it to withstand the bombs? A historian friend explained it was quite simple. It housed the plans for the V1 flying bombs and, more importantly, the V2s – the grandmothers of today’s missiles. Not to mention the blueprints for the Messerschmitt Me 262, the world’s first jet aircraft. The Allies had decided not to bomb that building, considering the power and wealth those plans represented. Hospitals and schools were irrelevant to them. The lives of ordinary people, as always, were worth much less than the design of a jet plane.

I was, of course, well aware that to the US government and its allies, the lives of common people meant nothing, especially those from foreign countries that had no bearing on their national politics and, even less so, in a war. Despite being well-versed in the United States’ attitude towards South American countries, I often found the organization of the GDR government unsettling. Even though they had rescued me from the oppression of the Chilean dictatorship and provided a comfortable life in Berlin, observing it with my values made everything seem so rigid, with little capacity for change and even less for accepting criticism. The immense political weight of the Stasi, the German secret police, was also troubling. I was now not only on the side of those who held power but also among those who could live comfortably. Yet there were moments when I saw stark similarities to Pinochet’s Chile – the lack of many freedoms, but worse, the iron grip of the government over its own citizens. It churned my stomach. So, I focused on working to fight against the dictatorship back home. These contradictions weren’t the reason I left Germany, but they influenced a decision I had to make later.

It was 1977, and the Chilean Socialist Party split into two factions: the pro-Latin Americans and the pro-Soviets. Even if I had never known East Berlin, I would always have sided with the pro-Latin Americans, that much is clear. But the mere thought of Valparaiso or Santiago under a political structure like communist Berlin… to me, that was akin to endorsing Pinochet’s methods. So, I had no doubts about choosing my side, even if it meant losing my economic and political standing. The day of the vote came, and we, the pro-Latin Americans, were in the minority. As often happens, a purge swiftly followed, especially targeting influential individuals, and we were expelled from the party. Shortly after, the Germans politely asked us to leave the country, and once again, I found myself on a plane, forced to leave due to disagreement with government policies.

Spain

So, in late 1977, we journeyed to Madrid. It was akin to returning to my own land. I swiftly felt at home, and not merely because of the shared language of Spanish. It was more the familiarity of the flaws I had known in Chile, which also existed there. Spain’s concept of aid for refugees, particularly leftist ones, was nonexistent. Thus, we Chileans expelled from the Socialist Party organized ourselves for mutual assistance, which ensured we had a residence upon arrival – a comrade’s home. A month later, I started working for the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), the only Spanish organization assisting Chilean socialists.

I was presented with two job offers. One as the head of coordination for socialist deputies in parliament, the other as the director of culture in Móstoles City Council. Weary of political wranglings, I chose the latter. It was a gratifying and fruitful role, leading to the creation of the Municipal House of Culture and the Móstoles Municipal Orchestra. I believe I did substantial work, using culture to reinforce the value of participating in democracy in a town that had grown rapidly yet was nearly abandoned by institutions. It lacked even a public school or hospital, facilities the residents would demand later. I hope my efforts contributed to making these happen.

The job in Móstoles also enabled me to save enough to invite my mother and sister to visit. Their arrival at the airport was a moment of pure joy.

«I told you we’d meet again,» my mother said as she hugged me.

«Thank you, Mum. There were times I wasn’t so sure. So, thank you.»

Those days were especially beautiful when my younger son and daughter, now teenagers, visited from England, and I had most of my family together for a few days.

After five years, I moved to Madrid and worked for the Community of Madrid, training female leaders. As an expert in adult education, I developed a specific curriculum for the training of women leaders, adapting techniques I learned from a Colombian guerrilla to the reality of Spain, particularly Madrid. These concepts were novel in post-Franco Spain. I managed to transform a group of ordinary women into strong, empowered leaders. A side effect of this training was that many of them left their husbands, realizing the limited, subjugated lives they were living.

Madrid was a tremendous experience for me. From teaching at the National University of Distance Education (UNED), where I learned to study and work remotely, to setting up a social projects company, encompassing all the business aspects involved.

Much of my work was directly related to politics. Even if it was just knowing the right people in decision-making positions, it led to a peculiar problem I gradually became aware of. It was something odd. If a project or company started doing well, suddenly and inexplicably, it lost interest. I concluded that a Chilean without significant patrons was not allowed into the influential, powerful, and wealthy club of Madrid’s politics. Once I understood this, it didn’t bother me. Despite feeling comfortable in Spain, I missed my country, my people, and my family. The dictatorship had fallen, so I explored the possibility of returning, and some doors opened.

Return

Cerro Aconcagua

The Santiago I arrived in was markedly different from the one I had left years before. It was a city dominated by networks of mutual support that more closely resembled a mafia than a helpful community. Yet, without integrating into these networks, progress was nearly impossible. I joined the socialist networks, and my reputation as a historic socialist figure opened doors to ministers’ offices, allowing me to present various high-quality projects, a skill honed in Madrid. This enabled me to settle down, but Santiago’s air pollution took a toll on my health. The doctor offered two options: a life dependent on pills or relocation to a place with cleaner air, like Valparaíso.

In Valparaíso, the newly appointed governor happened to be the younger brother of a dear friend murdered during the dictatorship. I reached out to him, and he remembered me well. Learning of my situation, he wanted me in his cabinet, valuing my experience.

«Of course, I want you on my team,» he said at our meeting. «I need someone close, honest, and trustworthy by my side. You are a party stalwart, respected by the base for never having sold out. We’ll make a great team.»

He helped me establish myself in my city with a significant role in the regional government. During this time, I also met my future partner and love of my life, a woman of extraordinary political vision, with whom I still enjoy engaging conversations and debates.

Working in the Valparaíso government was rewarding, but politics began to wear on me. Despite my immediate circle being well-off, dealing with numerous individuals obsessed with money and power started to take its toll. I’m convinced that such a mindset at such levels is a legacy of dictatorships, a sentiment I had also experienced in Spain. So, I began teaching at the university, where I could lecture on the Theory of Complexity, a subject I was introduced to in Madrid through a talk by its leading proponent, Edgar Morin. This philosophy, breaking with the conventional yet aligning perfectly with my view of life and people, has evolved over the years. It now aligns more with ecology as a philosophy or way of life than with the leftist values I defended in my youth.

Despite my disillusionment with politics, the initial uprisings of Chilean students injected some vitality into me, leading me to write a book, «Why Does the Capitalist System Survive?», based on the Theory of Complexity. At first, I believed these revolts wouldn’t gain much traction, seeing them merely as a few adolescents railing against the epitome of neoliberal capitalism. However, their movement persisted and gradually garnered broader societal support. They drew inspiration from the Mapuche people, who, after more than five hundred years, remained unconquered and continued to fight for their way of life. On my way to work, I observed young men and women in what seemed like small assemblies in the alamedas and plazas, where discussions and rap music resonated at equal volume. I never imagined that these gatherings would not only lead to a drastic governmental shift but also ignite a struggle for a new constitution.

«Chile. The country that saw the birth and death of neoliberalism.»

I didn’t believe it at first, but events were unfolding at a breakneck pace, and then one day, something happened that for much of my life I thought I would never witness. A President of Chile declared:

«As Salvador Allende foresaw nearly 50 years ago, we are once again, compatriots, opening the grand boulevards for the free man, the free man and woman, to build a better society,» amid cries of «Viva Chile» and chants of «Se siente, se siente, Allende está presente» (It’s felt, it’s felt, Allende is present).

That day, amidst my tears of happiness, hope and faith in my people were reborn. It seemed each tear fell like droplets of water, revitalizing that old tree I remembered from the Chacabuco concentration camp. Those tears rekindled a sense of purpose in my life. I had been one of those who contributed something that enabled that young president to speak those words. Like that ancient tree, the elder of the village, I felt reborn.

My thanks to my father for allowing me to bring to light many things that were previously only personal memories and to alter or embellish them as I pleased. Also, I would like to express my gratitude for all the support and initial reading provided by Loreto Alonso-Alegre and Dolores Póliz for their editing of the original Spanish text, which adds a touch of perfection to the narrative. Lastly, but not least, I would like to thank my son Alberto Ahumada for providing me with very good ideas.

0 comentarios