Museums

I’ve always loved museums, especially those of archaeology and history. Seeing how our ancestors lived is simply fascinating, especially when you realize that what’s in the museum is just the tip of the iceberg. The remaining 89% simply remains unknown, or so it seems at first glance.

Humitas – Boiled corn cakes

Once upon a time, in a faraway land known as Chile, my father and mother, in defense of their ideals of justice and freedom for all, found themselves imprisoned by a cruel and bloodthirsty dictatorship. After spending days, perhaps months, with close relatives, my sisters and I ended up living with our paternal grandmother in a small countryside village named Codegua. My grandmother owned a large house in a nearby city, but the modest home in the village was inexpensive and easier to maintain, and with enough land, we were ensured food on our table.

For me, it was a transformative change. In the city of Valparaíso, I was a child with parents who were educators, politicians, unionists, scientists—one an atheist and the other a Gnostic—and quite intellectual. I lived a middle-class life, constantly surrounded by books. For my age, I knew much about the world, but through the written word, so living with a grandmother who believed in God, was Catholic, and thought the only way to be a good person was through hard work marked a significant shift. I admired and loved my grandmother deeply, thus her eccentricities, like praying every night, I accepted without question, never pestering her about why she did it and what it served. But one day, my curiosity got the better of me, and I asked.

«But what do they teach you in school?» she replied. Before I could answer, she handed me a piece of paper with the image of a very strange man and two days to learn the text.

«It’s the Lord’s Prayer. It’s a prayer,» she said, without further explanation. Two days later, I knew it by heart and recited it to my grandmother. After finishing, I inquired:

«What is a prayer?»—

«A way for normal people to speak with God. Some people talk to a priest, but they’re all liars,» she retorted.

You can imagine the flurry of questions that erupted in my mind. Speaking with God? How could that be possible? I was aware of people who believed in a Christian god named Jehovah, but in my mind, this mythological being was in the same category as Thor, Zeus, Jupiter, or Amun-Ra.

«Can you really speak with God?» I asked, astoundingly surprised.

«I speak, and he doesn’t reply, but sometimes he listens. Try it. You just need to say the Lord’s Prayer and ask for something,» she concluded, effectively ending the conversation. I couldn’t inquire further about the dishonest priests. In my life, I had only known one priest. His name was Michael Woodward, an Englishman and very friendly. He was a friend of my parents and had been tortured to death by the Chilean dictatorship on the training ship Esmeralda. I couldn’t picture him as a lying priest.

Almost a month later, I had the chance to test speaking with God. The teacher announced a Chilean history exam for the following day. Being new to this school, I wasn’t aware they conducted exams at the end of each semester, as I was accustomed to end-of-year exams in previous schools. It was the perfect scenario to employ the Lord’s Prayer.

That night, I knelt as my grandmother instructed, repeated the Lord’s Prayer, and asked God to help me pass the exam the next day. Obviously, I didn’t study at all, as that would not prove God’s power.

The next day, facing the exam, I only knew the topic of one out of four questions. The others were completely foreign to me, but trusting God was on my side, I drew upon my imagination and crafted tales worthy of a seasoned storyteller. A week later, the teacher handed me my grade, and I had passed comfortably. I couldn’t believe it. How was it possible that reciting a bizarre prayer, with no connection to primary education, to a mythological being could work? I admit, I felt as though I could communicate with beings of extraordinary powers that were utterly beyond understanding, and it scared me. What if I made a mistake and it came true? It was like the first free hit of a drug from a dealer, knowing exactly why it’s free. My logical mind was deeply frightened, and I decided never to pray again, a resolution I managed to keep. What I did gain was a profound respect for my grandmother. This retired lady who could converse with titans by merely repeating nonsensical words. So, when one day she tasked me with a peculiar job, I didn’t utter a word of protest.

I had to move a massive stone closer to where my grandmother and my older sister were shucking fresh corn, and clean it thoroughly. I tried to move it, but it wouldn’t budge an inch.

«Paloma, can you help me with this? It’s really heavy,» I asked my sister.

«Why do you want to do that?» she replied. A totally understandable question to which I had no answer other than:

«Grandma asked me to.»—

«Really? Alright then,» she said, accepting the situation as if it were the most natural thing in the world. I suspected that my sister Paloma already knew about grandma’s ability to talk with invisible, superpowerful beings. We exerted ourselves greatly, but the stone, calm as ever, remained in place.

«Grandma, we can’t move the stone. It’s too heavy,» I told my grandmother.

«It’s okay. Put some water and a bit of soap in a bucket, and with the scrubbing brush for washing clothes, you must clean the stone well. Not just the big one, but the small one next to it as well,» she replied.

«The small one too?» I thought. It seemed odd, but my grandmother could speak with gods, so I followed her instructions.

«When they’re clean, rinse them, and then come for a bowl of shucked corn,» she instructed. I cleaned the stones, pondering what connection they could possibly have to the corn. After finishing, I went to where Paloma and my grandmother were and informed them that the stones were clean. She returned with me, carrying a bowl filled with freshly shucked corn and a large plate.

The grand stone bore an uncanny resemblance to a barque, stretching some 30 centimeters or more in length, with a crevice on its inner side nearly as long as the stone itself. The smaller stone fit perfectly into this indentation.

My grandmother placed the large plate at one end of the stone and instructed me to stand on the opposite side. Then, with a large spoon, she scooped some fresh corn and deposited it into the stone’s crevice.

«Now, with the smaller stone, you must grind it well. Crush the fresh corn as you move the smaller stone back and forth with both hands. Once you’ve ground a bit, push it onto the large plate. Come on, there’s much to grind. We’re making humitas, and I want them ready for the meal.»

I attempted the process, finding it simpler than anticipated, and realized it bore no relation to my grandmother’s ability to converse with gods.

«Like this?» I asked.

«That’s it. Very good. Once you’re done with the bowl, come back for more.»

I set to work, drawing the smaller stone towards me and pushing it away, crushing small portions of fresh corn and grinding them. Gradually, I fell into a monotonous rhythm that allowed my mind to pilot spacecraft in grand intergalactic adventures, while my body remained in my grandmother’s backyard in Codegua, grinding fresh corn. Just before a significant battle near Sirius B, I finished the last of the bowl’s contents. Amidst the space adventures, I hadn’t noticed the fatigue setting in. My arms ached for several days afterward.

A fortnight later, my grandmother decided to make pastel de choclo, and it appeared I had become the official grinder of fresh corn kernels. Thus, I was back to thoroughly washing the stones before grinding the fresh grain once again. My arms ached for days once more.

Some time later, my grandmother announced that my aunt would be visiting us, and her fondness for humitas meant it was once again time to grind. I must confess, with each session, the blend of pulp, husk, and milky juice from the corn kernels improved under my hands. This time, my arms ached for a shorter duration.

Besides grinding corn, another of my duties was to kindle the fire in the kitchen each morning. I had to clear the ashes from a square of bricks and cement. Then, starting with small twigs, I had to have a good fire going by the time my grandmother rose to prepare breakfast. Directly above the fire hung a chain from the ceiling, fitted with hooks at various heights. This was how my grandmother regulated the amount of heat reaching the pots.

One day, wandering through the house, I saw my grandmother emerge from a room that was always locked. Curious, I asked her why.

«It gets dirty easily. Dust always finds its way in, and the floor becomes covered with dirt.» Upon entering, I understood her concern. The rest of the house had compacted dirt floors, but this room boasted polished wooden floors, elegant furniture, paintings on the walls, a table, and a noble black wooden cabinet where glasses and plates adorned with images that seemed to tell tales were kept.

«Your grandfather made the cabinet and the rest of the furniture. God rest his soul.»

«They’re very beautiful,» I replied.

«Yes. He was very skilled with wood.»

I turned and looked behind the door. My eyes couldn’t believe what they saw.

«A gas cooker!» I exclaimed, nearly shouting, looking back at my grandmother.

«Yes. I use it when I need to bake something.»

«But… but… It’s not fair. Why do I have to get up every morning to make the fire to warm the milk if you have this here?» For the first time, my grandmother looked at me as an adult and explained.

«A teacher’s pension isn’t enough to feed two adults and three children. That’s why we live in this house and not the larger one in the city. Here, the old stove still works, and the wood we gather from the trees is free. Gas cylinders cost money, and I prefer to spend it on more important things.»

I appreciated that explanation. My grandmother treated me as an adult, and I understood the responsibility that had fallen to me. I smiled, wiped my feet on a doormat at the entrance to the magical room, and stepped in.

«Since you’re there, pass me the bread knife. It’s in the drawer next to the cooker.» Opening the drawer, I encountered another surprise. Among the knives and other kitchen utensils was a disassembled meat grinder. The kind you clamp to the edge of a table, where you put the meat in the funnel at the top and turn the handle, which pushes the meat through a screw system forcing it out through small holes while cutting it. My surprise wasn’t that my grandmother ground meat, but because, in Chile, this same device was used to grind fresh corn. I picked up a piece of the device and went to my grandmother.

«Why do I have to use those stones when you have this?» I asked, frustrated.

«You’re too skinny. You need to build your muscles,» she replied.

Rather than pondering whether I was thin, this answer confirmed that my grandmother was quite ordinary. The superwoman who conversed with gods began to fade and finally disappeared when I learned that the history teacher was left-leaning. I suspect he perfectly understood my situation and gave me a chance with that exam. God, as my grandmother said, never answers.

Much later, I was with my wife visiting our two children living in Madrid, and we decided to visit the National Archaeological Museum. I love museums, and sometimes I come across surprises, like when in the Stone Age section, I saw a stone shaped like a boat with a crevice from stern to bow, and beside it, another stone used for grinding. I turned to my son, the youngest of the family, who was studying for a master’s, and said:

«Bloody hell! Look at this, I used one just like it when I was little to grind fresh corn.»

My son came closer to see what I was talking about. He looked at me and said,

«Please, Dad. I know you’ve used ancient technology, but this is the Stone Age!»

We both burst into laughter, recalling the events from years earlier at the Euskal Encounter in Bilbao.

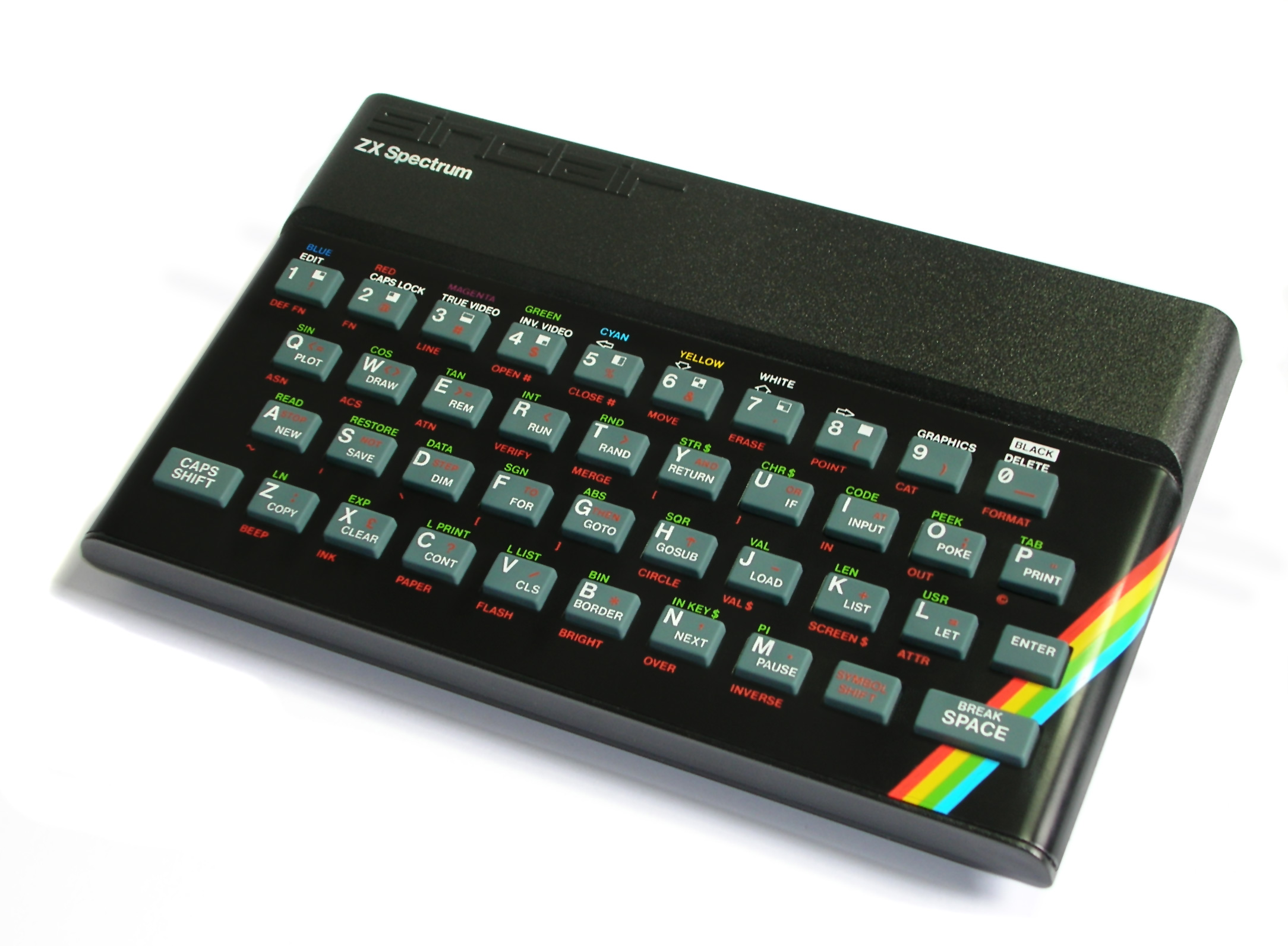

Euskal Encounter

If you are a geek of computers or games, you’ll be familiar with what those within our circle call ‘The Euskal’. For the uninitiated, it’s an annual convergence where hundreds gather, toting their personal computing devices and an assortment of technological wonders, weaving together a tapestry of events for sharing and revelry—a festival spanning three days, wherein participants eat and slumber within this communal domain.

I’ve ventured into its embrace for the full duration just once, yet on several occasions, I’ve secured a day’s passage to join my children, friends, and workmates. From my first foray, what struck me was not merely the camaraderie but the palpable trust among all who gathered. It allowed for serene exchanges with any soul, stranger or not, and bestowed the confidence to leave your latest model phone, a gaming mouse of the highest definition, or those exceedingly crisp and costly headphones at your station, step away for a coffee, and upon return, find everything just as you left it, untouched. A realm positively brimming with goodwill.

My initial pilgrimage was to see my offspring, basking in the event’s three-day spectacle. At one moment, my younger son, a lad of about twelve, urged me:

‘Look, Dad, come with me. I think you’ll find this fascinating. There’s a museum.’ We meandered through aisles bordered by tables burdened with computers of every ilk, past youths adorned in everything from casual tracksuits to elaborate costumes of their beloved video game characters, until we arrived at a secluded corner of the vast warehouse. Shielded by folding screens lay the museum. A haven for computers spanning the ages. As I stepped through the threshold, the first words I uttered were,

«Look, I’ve used one of those before,» my son gave me a glance for a moment.

«It’s not that old,» I said, responding to his look.

«Look, I’ve used that one too… and that one as well. I swear it’s true,» I said after noticing his incredulous gaze once more.

As we progressed down the line filled with ancient computers, it felt as though we were travelling further back in time, encountering ever older hardware. When we passed by an Amstrad PC1512, I remarked,

«That was my first PC. It was reasonably priced compared to everything else. Your grandfather bought it for me. It would crash every time it got too hot. I came close to throwing it out the window several times after losing hours of work.»

Upon reaching a Compaq Plus Portable, I explained to him how they were so reliable that companies would use them as servers. A bit further on, I told him that the only Sinclair Spectrum worth having was the one with a cassette. That way, you could save your code; otherwise, when you turned off the PC, everything was lost. With each revelation, my son’s gaze grew increasingly bewildered, and I couldn’t quite fathom why.

Near the end of the museum, I encountered an old friend.

«Look, look. This is an IBM PC Junior. It was my first work computer,» I was about to share that it came with the first MS-DOS as its operating system and had two floppy disk drives where I used Lotus Symphony, but I could tell I was getting carried away, and my son told me,

«But Dad, please, this is a museum. You can’t be that old.»

It was the second time I felt old. The first was in a clothing store where the sales assistant, only slightly younger than me, addressed me formally.

IMH – Instituto de Máquina Herramienta

A few years back, just before my son dropped that comment that stuck with me, I was working in Elgoibar, Gipuzkoa, at the IMH. We were setting up their first Domino mail server on a PC that was pretty standard for its time. This foundation was all about teaching machine tool technology to the local youth, considering Elgoibar’s rich history and excellence in the field. My visits were mostly about tinkering with their mail server, fixing this and that, or upgrading to whatever new version IBM had just rolled out. It was all IT, through and through.

One day, they called me up because their mail server PC was running out of elbow room, and they’d gone ahead and bought some beefy machines, complete with disk arrays and racks. So, I left home in Getxo early to meet Eneko, the foundation’s IT lead, first thing in the morning.

We headed down to the ground floor of the main building, took a right, and stepped into this huge empty room, about the size of a basketball court. At the far end was a door leading to a small room where the new hardware sat, all shiny and configured, just waiting for the mail server to be moved over. I got everything set up and by the end of the day, left the machines to do the heavy lifting of copying files, the slowest part of the job, done best when no one needed to access their emails. The next morning, everything had gone smoothly, so I switched off the old server and let the new one take over. I promised to check back in a few days.

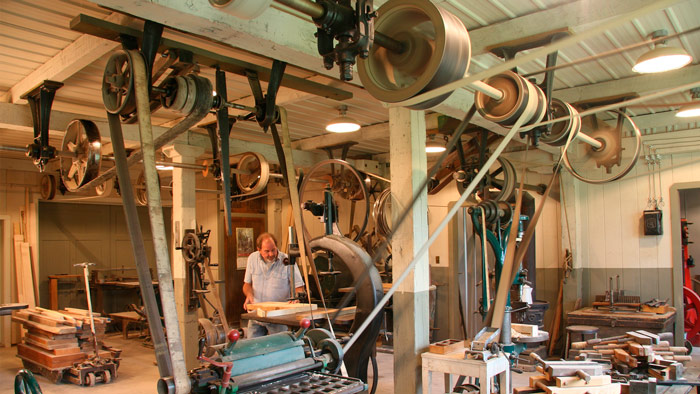

A week later, coming back to that large room, I found it transformed. Now, it was filled with tubes and huge belts scattered all over the floor, which caught my eye because they looked oddly familiar. Standing by the door, taking it all in, a voice broke my concentration.

«You wouldn’t guess what this is,» I hadn’t realized there was someone else in the room. It was one of the teachers I’d occasionally see while grabbing a coffee.

«It does remind me of something,» I replied.

«I doubt you’ll guess. You’re young and work with the servers over there. You probably won’t get it,» he challenged. «No one has so far.»

Looking around at the pieces, whatever they were part of, it was clear it was something big, as they covered much of the room’s floor. Suddenly, it clicked.

I was about six or seven when, during summer holidays spent at my grandparents’ in Rancagua, I discovered that a few doors down from Zañartu Street lived my grandfather’s brother, Uncle Segundo. He was my dad’s uncle, but everyone called him that. I remember Uncle Segundo’s house was L-shaped, with the short part facing the street. The long part had multiple rooms, with, I believe, the kitchen at the very end. The rest of the area was open. At the back and to the right was a space where my father’s uncle had his workshop. My first visit there was quite formal, as I was with my grandmother and had to sit quietly in the front room, listening to conversations about people I didn’t know. Bored, I drifted into my imagination, becoming a famous engineer who’d invented a faster-than-light engine, only to regret it as humanity underwent a drastic political, economic, and cultural shift that I found unsettling.

«Alvaro, respond to Aunt Orlanda,» my grandmother’s voice, tinged with seriousness, brought me back. I suspected she had called me out before. I looked up to see Aunt Orlanda, not annoyed but smiling warmly, understanding my daydream.

«Hehe, don’t worry, Maria. He’s definitely family. Sometimes I get the same look from Segundo. You were lost in thought, right?» she asked, to which I nodded.

«Would you like some mote con huesillos?» she asked next. I immediately said yes. Mote con huesillos is a Chilean delight, especially on hot days—a drink made with peaches and barley, boiled with sugar and drank cold.

«Come with me,» she said, and we left the front room for the open area where, on the left side, a row of doors led to the back. The last door was open, and Aunt Orlanda entered, while I stayed, drawn to the sounds of work from the opposite side.

«Here,» she handed me a freshly made glass of the drink, noticing my gaze, «That’s your Uncle Segundo, working on one of his projects. Let’s go back to Maria; she’ll be waiting.»

Back with my grandmother, my focus shifted entirely to enjoying the mote con huesillos.

Over a week later, just before noon, my grandmother, having returned from shopping, called out to me, «Alvaro, come here. You need to take these onions to Aunt Orlanda. She lent us some last week, and now I want to return the favor,» she said, handing me a bag filled with onions. Little did I expect those onions to feel like they were made of lead. «Lunch will be ready in about two hours. Make sure you’re back by then,» she instructed, which struck me as odd given the short distance to my aunt and uncle’s house.

Leaving the kitchen, I stepped into the open area with a small garden and had to stop to rest almost immediately. I looked at the bag—just four onions, but they were massive.

«Don’t be long,» my grandmother called from the kitchen. «Orlanda might need them soon.»

I picked up the bag and continued on my way, turning right to head towards the covered courtyard, passing a room without giving it a second glance—a room that, in the future, would introduce me to Aunt Carlota’s ghost. In the courtyard, I set the bag down again, my arms aching. After a short pause, I picked it up, made it to the courtyard’s door, and stepped outside. It was January, and the summer sun was merciless. I tried carrying the bag in various positions, but over the shoulder seemed to work best. My uncle Segundo and Aunt Orlanda’s house wasn’t more than 30 meters away, yet I had to stop and rest multiple times. Clearly, physical labor wasn’t my forte.

Upon arrival, I knocked several times, imagining Aunt Orlanda might be at the other end of the house. After a while, she opened the door, and without a greeting, I stepped in to escape the relentless sun. Inside, I turned to her and said, «Hello, Auntie. Gran sent these onions over,» finally setting the bag down with relief.

«What a good boy,» she exclaimed. «Come with me, and bring the onions to the kitchen.» My face must have betrayed my feelings because she burst into laughter.

«Don’t worry. I’ll take them,» she said, lifting the bag effortlessly. «Come. There’s still some mote con huesillos left from yesterday.» I followed her, much happier now.

I was waiting at the kitchen door when suddenly, behind me, an engine started to cough to life, its roar filling the air like an old train gathering speed. I turned to look, but whatever was making that noise was hidden within Uncle Segundo’s workshop.

«Here,» Aunt Orlanda handed me a cold glass filled with that wonderful nectar. «If you want, go see what Segundo is doing. I think you’ll like it.»

I approached the workshop, which had two large doors, one of them open. The sight that greeted me is etched in my memory forever. Uncle Segundo was shaping wood on a lathe, but it wasn’t the lathe itself that captivated me.

I found myself standing before a marvel of engineering that seemed to bridge the gap between the past and the future. Uncle Segundo was at his lathe, working a piece of wood into something undoubtedly beautiful. Yet, it wasn’t just the craftsmanship that held my attention—it was the intricate machinery that brought the lathe to life. Behind the simple action of shaping wood lay a complex ballet of mechanical components: a series of belts and pulleys that breathed life into the workshop.

The heart of this mechanical organism was a diesel engine, its steady hum a testament to the ingenuity of a bygone era. This engine connected to a series of belts that stretched up to the ceiling, where they met with a network of pulleys. These pulleys, in turn, were connected to various machines throughout the workshop, each performing its unique function yet all synchronized in perfect harmony.

From one pulley, a belt descended to drive the lathe where Uncle Segundo worked, its rhythm steady and reassuring. Another belt veered off to power a drill press, its bit spinning with precision that was both necessary and hypnotic. Further along, a third belt connected to a saw, its teeth cutting through wood with a sound that was almost musical.

This network of belts and pulleys was more than just a means to transfer power; it was a living, breathing entity, with the diesel engine at its heart pumping life through its veins. The air was filled with the smell of sawdust and oil, the sounds of industry and creation melding into a symphony of productivity. It was a scene that connected the dots between the tactile and the mystical, where the roar of the engine and the dance of the belts seemed to whisper secrets of the past and possibilities of the future.

I stood there, mouth agape, the mote con huesillos forgotten, as the engine suddenly stopped, silence reclaiming its territory.

«Are you Alvaro, Padriag’s son?» Uncle Segundo asked, inspecting what seemed to be a furniture leg, pulling me from my reverie into a moment that felt suspended between the mundane and the magical.

«Yes, my grandmother sent some onions over for Aunt Orlanda,» I replied, feeling I should explain how I ended up there, my gaze quickly drawn back to the mesmerizing system of pulleys and belts.

«Do you like the workshop?» Uncle Segundo asked, a hint of pride in his voice.

«Yes, a lot,» I said. «Do all these tools work off a single engine?»

«Yes, all of them. I have them organized into groups of two machines. It’s a line shaft system and it’s been here for a long time,» he explained with a sense of satisfaction, beginning to detail how he could connect and disconnect the machines or groups of machines simply by engaging or disengaging the belts. He mentioned that it was a system invented during the Industrial Revolution in England, but the original engines were steam-powered.

This was the explanation I gave to the teacher at the IMH, who listened with a look of surprise.

«You’re the first one to get it right. I’ve asked all the teachers, even the oldest ones, and no one knew the answer. Then you come along, someone whose work has nothing to do with machine tools, and you know it. Well done. You’ve really made my day.»

«Thank you,» I responded. «My great uncle taught me how a belt-driven workshop operates. He had one.»

I’ve seen workshops like that again, only in museums, and every time I do, I remember Uncle Segundo. Truthfully, I wish I had had the chance to know him better.

Speaking of museums, a few years later, all those tubes, pulleys, and belts became part of the IMH Museum.

My thanks for all the support and the initial reading of the original text in Spanish go to Dolores Póliz for her editing that adds a touch of perfection to the story. Also, to Loreto Alonso-Alegre for her invaluable comments.

0 comentarios