Ethereals

In these tales, I recount encounters with beings beyond explanation, entities that have intersected with the fabric of my life at various junctures. Yet, it is important for me to state unequivocally that I do not subscribe to the existence of ghosts or specters. Nevertheless, as you will soon discover, I hold a trove of reasons that compel me to believe in phenomena that defy our conventional understanding of reality, extending beyond the reach of even scientific explanation.

The Lady of the Room

I was about 8 years old, spending my holidays with my grandparents in the city of Rancagua. They lived in an adobe house with thick walls in the old part of the city. The house was ancient and, to me, also enormous. It must have been at least a hundred years old, which for a small child is an eternity. Though in Chile, old houses rarely lasted longer, thanks to the earthquakes.

I loved that house. It gave me a strange sense of security with its old adobe walls over a meter thick that had withstood more than one earth tremor and kept the house cool in summer. The roof had tiles, something I only saw in books when the rest of the year I was in Valparaíso in a newly built bungalow on Cerro Placeres. When I told my grandmother about it, she said the tiles were nothing but trouble.

“Why?” I asked, looking at the roof that was as still as the day before.

“The wind and cats move them,” she replied.

“The cats? Why?” I asked, not imagining what could be so interesting about a tile for a cat.

“They look for bird or mice nests.” she asserted.

I was already starting to imagine a bunch of winged mice coming out of a nest when she asked, “Do you have anything to do?”

I knew the answer to that question should be “Yes, grandma. I’m very busy,” but I’ve always been bad at lying, so I told her, “No. Why?”

I expected her to say I should do something useful, like study or help someone older, and she did, but with something more entertaining.

“When you see a cat on the roof, grab the hose and give it a good squirt of water. Searching for nests, they move the tiles, and when it rains, there are leaks in the house.”

It was clear that helping my grandmother was much more entertaining than the things my grandfather asked me to do, like study, clean, and stay quiet without talking. My sister, who was a year older than me, got along much better with him, but I didn’t. So, I spent almost all the time playing cat and mouse with him so he wouldn’t see me and think of something I should do. I decided to help my grandmother and spent days climbing on a chair or wherever I could, to see if I could spot a cat, but I never saw one. One day, on my cat-hunting round, I saw my grandmother coming down a ladder she had placed to climb up to the roof. Not knowing grandmothers could climb roofs, I approached, intrigued, wondering if she had seen a cat. When I reached her side, I mentioned it. She looked puzzled until she remembered what I was talking about.

“Oh, no, no. I was putting the charqui on the roof to dry in the sun,” she said.

I, being a “modern” and very inquisitive child, said, “What’s charqui?”

“A type of food for long journeys,” she replied.

“What kind of food?” I asked as she walked away to one of her many things she always had to do. I rarely saw my grandmother doing something to relax. She turned and said, “Aren’t you supposed to be keeping the cat away?” with the look no longer of my grandmother but of a teacher with years of experience teaching annoying and inquisitive children.

“Grandma, can I have some of that charqui?” I asked, trying to sound as formal as possible and using the affectionate name my sisters and I had for my grandmother.

“Charqui,” she corrected. “Yes, just one. Go up and take one of the ones on the right that are ready. Make sure not to move any tiles.”

Her response surprised me. No one had ever allowed me to climb a roof before. In that second, my grandmother won a piece of my heart, and she kept it forever. I still remember the moment fondly, but not just for climbing the roof, but because it started a small adventure of those you never forget and leave you thinking for the rest of your life.

It was a homemade ladder made of two straight and long tree branches, with short branches as rungs. I climbed up step by step carefully, and when I reached the height of the tiles, a whole new world opened up that I never thought could exist. An enormous part of the house, full of sun and open sky, where no one would be forcing me to study. I took my first step and felt the fragility of the tile under my weight. I decided that the most logical thing was to step on the ones that made the gutter since they seemed to have more support underneath. I looked to the right and saw on top of some papers, strips of different thicknesses of something dark no more than five centimeters long. I sat on a tile before taking one. I felt safer sitting than standing on the tiles that seemed very fragile since they were not like the modern ones that fit together like a puzzle, creating a solid and quite strong structure. These were all independent and moved each on their own. I understood why it was easy for the cat to move them.

I picked up one of the charquis and sniffed it. It smelled faintly like barbecue meat. I bit into it, and it was like biting a tree branch. At first, it seemed to give way, but then it was hard as a shoe sole. The initially very salty flavor ended with a touch of overcooked barbecue meat. I doubted whether that could really be eaten, but it wasn’t an unpleasant taste, so I kept chewing with my molars, and little by little, it started to become softer, enough to tear off a small piece. It was like eating an old and very salty chewing gum. While chewing, I looked around. From that height, I could see the shape of the whole house, which was a kind of square U with one side longer than the other. The center of the U was open to the sky, where there was a small garden facing the dining room and kitchen. From where I was, I could just see the kitchen door and my grandmother doing something inside. It was like being in another world.

“Álvaro, what are you doing up there!” My aunt’s shout brought me back to reality, giving me a fright.

“I’m eating charqui and taking care of the tiles,” I replied.

My aunt, who knew me well, didn’t ask me anything about that tile care and said, “Get down from there; you could fall.”

But I had a magic phrase that could be a safe-conduct for any situation, even with my father and mother, “Grandma gave me permission.”

My aunt looked at her mother, and she said, “You can’t treat children as if they were made of glass. Let him learn.”

“Be careful,” was all my aunt said to me. When the matriarch of the family gave her opinion, it was not discussed. I liked that my grandmother was on my side. Her years of experience as a teacher showed. Although I already knew that. She taught me to read at four years old, and at five, I was already reading my father’s science fiction novels. All thanks to her.

I realized that the side of the house where I was, was a bit longer than the side where the kitchen was. I had seen a door in that part, but I had never paid much attention to it. That section of the house opened onto an open area, part roofed, which had rooms where my grandfather kept his tools. They called it the courtyard, and I always thought that behind that door, there would be nothing more than tools or remains of my grandfather’s many inventions. Something told me it was a good time to get off the roof and go look at that room.

I stood up and carefully approached the edge where the ladder was. Suddenly, going down seemed much more difficult than going up. My grandmother was still in the kitchen but was focused on her things. I grabbed the top of the ladder and carefully turned to put my foot on the highest rung. I could feel my grandmother’s gaze on my back, and that gave me more security. I started to go down very carefully, making sure to put my weight well on each rung, as I always saw my sister’s cat do when walking through difficult places. Finally, I reached the ground. I turned and smiled at my grandmother, who also smiled at me.

I walked following that side of the house to enter the covered courtyard. Immediately to my left was one of those rooms, and the door was slightly open. I approached and pushed the door, but what I saw was not what I expected. Instead of being a room full of junk and boxes, someone lived there. There was an iron bed with those brass balls at the corners, with the quilt thrown to one side as if they had just gotten up, a nightstand, a wardrobe, and a piece of furniture with things that looked like women’s, like a hairbrush just like my grandmother’s. I was very surprised to see all that. I knew everyone’s rooms, and no one slept on that side of the house. Where was that person? I had been on the roof very close, and from there, I would have seen anyone going to the bathroom. I carefully left the room, although I don’t know why, and headed to the kitchen to ask my grandmother who slept in that room.

As I came out, I saw my two sisters at the foot of the ladder looking towards the kitchen, and voices arguing were heard. Paloma was a year older than me, and Daniela was almost four years younger. Both seemed worried. When I joined them, I saw that the ones arguing were my father and my grandmother.

“What’s happening?” I asked them.

“Dad found out you were on the roof,” Paloma, my older sister, replied.

“But he wasn’t home. How did he find out?” I asked them. Neither answered, but Paloma and I turned to my younger sister Daniela, who looked at us offended.

“I didn’t do it,” she said. Daniela was about four years old and always knew everything that was going on and where all the lost things were. She also told everything to our mother, but on the other hand, she never lied. The voices of the adults rose a bit in tone.

“But son, you did the same when you were little.”

“And I got a good scolding when I moved a tile, not to mention when I fell.”

“And you learned to be careful. Let it go already; I’ve watched him, and Alvaro is careful.”

“The child’s responsibility is mine, and even though we are in your house, you cannot make such decisions without my consent,” my father replied angrily.

At that moment, something happened that I never thought I would see or even that it was possible. My grandmother slapped my father hard. Time seemed to stop while the sound, like the crack of a whip, moved through the house. My sisters and I, at the same time, took a step back, trying to get away from that fight of giants.

“Never ever speak to me in that tone again! I am your mother, and you owe me respect. This is my house, and in your absence, I make decisions regarding the children,” my grandmother said with the voice of a matriarch. We didn’t wait to see what happened next. As if by magic and close to a quantum leap, the three of us were already at the other end of the covered courtyard, behind a huge drill that my grandfather had bought for a copper mine near the mountain range.

“She slapped Dad,” Daniela said, still assimilating what had happened.

“You’re going to get a good scolding for that,” Paloma told me.

“It wasn’t grandma hitting dad. It was a mother teaching her son not to be rude,” I replied.

“But it’s Dad,” Daniela said.

“But before that, he’s Grandma’s son.”

We had never seen our father as someone’s son. Obviously, we knew that Grandma was his mother, but it never occurred to us that the mother-son relationship still existed. To us, they were simply two adults in the family. After a while, we got bored and returned to the house. Before reaching the small central garden, we passed by the door of the room.

“Do you know who sleeps there?” I asked Daniela.

“Where?”

I stopped. I was no more than three meters from the door.

“That door,” I replied, pointing with my finger.

“No one sleeps there. It’s full of Grandpa’s junk.”

“That’s not true. I just came from there, and it’s someone’s room. Look, come.” I replied as I approached the door and opened it, sure that the room was still empty since no one had passed by in all that time. The three of us entered. The room was exactly the same.

“Someone has cleaned all that up,” Paloma said. “A few days ago, it was full of dusty boxes.”

A metallic noise caught our attention, and the three of us looked towards the bed.

There was a very, very old lady full of wrinkles lying on the bed. She was covered with the quilt as if it were very cold, but the strangest thing was that she was looking at us with wide open eyes and a frightened expression. For a moment, I thought it was because we had entered her room without knocking, but I realized she didn’t have a surprised or angry face, but one of fear. A lot of fear.

I had never seen her before and suspected that she had not seen us either, so remembering the formalities that Grandma expected from us when she introduced us to her family or Grandpa’s, I said, “Hello. My name is Alvaro, she is Paloma, and she is Daniela,” I said, pointing to my sisters. This seemed to reassure her a bit. She looked at each of us for a long time, as if we reminded her of someone.

“We are Pádraig’s children,” I told her to give her a clue as to who we were.

She didn’t say anything. She turned and settled into bed. Then she closed her eyes and ignored us.

We stood for a while looking at her. Waiting for some kind of response or something that would let us know she was aware of us.

“Hello, ma’am. Are you alright?” Paloma asked, her voice echoing slightly in the room that seemed to hold more secrets than furniture.

“She’s not,” Daniela stated, her gaze fixed intently on the woman.

“Not well? How do you know?” Paloma inquired, a frown of concern creasing her forehead.

“No… She’s not here,” Daniela clarified cryptically.

“Who’s not here?” I asked, my curiosity piqued by my youngest sister’s enigmatic words.

“Well, she is,” Daniela said, almost whispering.

“Of course she’s here!” I responded, a bit more emphatically than intended.

“Don’t you see her right there?” Paloma added almost simultaneously, her tone blending disbelief and bewilderment.

Daniela simply shrugged and exited the room, her gaze lingering on the woman as if she were witnessing something for the first time. Paloma’s eyes briefly followed her younger sister before returning to the still figure on the bed.

“What a strange feeling,” she said to me. “Has it gotten colder in here suddenly?”

I hadn’t noticed any change; the room felt as it had when we first entered, shrouded in an atmosphere of timeless mystery. Just as I was about to respond, our mother’s voice calling us for tea echoed through the house. Paloma hurried out, seemingly grateful for an excuse to leave. I stayed a moment longer, my gaze fixed on the mysterious woman. Who was she? She appeared older than grandma, enveloped in a veil of deep, unspeakable history.

“Álvaro!” my mother’s voice, tinged with irritation, beckoned me back to the present. Time always seemed to pass differently for me.

Exiting the room, I gently closed the door. Through the narrow gap, I caught the woman’s eye watching me, a silent, observant presence. I smiled and waved goodbye before heading to the dining room.

In the dining room, everyone was already seated. I braced myself for the usual reprimand for being late, but instead, I was met with solemn stares from the adults and a silence that weighed heavily in the air.

The next day, curiosity led me back to the woman’s room near the covered courtyard. Knocking brought no response. “Hello! It’s me, Alvaro. Can I come in?” I called out, only to be greeted by the echoing silence of an unoccupied room.

I opened the door wider and entered. The bed was neatly made, but the room was empty. How did she move around so unnoticed? I left quietly, pondering her movements. The covered courtyard had a small pedestrian door, suggesting she might not be a relative but rather a tenant using this discreet entrance.

Later, discussing her whereabouts with Paloma, I was surprised to learn about a bathroom in the courtyard. “The courtyard has a bathroom?” I asked, intrigued by my unfamiliarity with every part of the house.

“Yes, come see,” Paloma led me behind the clay tank to a hidden bathroom, so compact that showering would surely soak the entire room.

“She must be renting the room,” I concluded with Paloma.

“Probably,” she agreed.

The bathroom seemed unused, dusty, and neglected – a stark contrast to the neat room. But understanding adults was often a puzzle in itself.

Weeks later, after another rooftop adventure, I passed by the room and heard a strong cough. “Hello? Are you okay?” I called, but received no response.

“It’s Alvaro. Hello?” I cautiously pushed the door open. Inside, the lady sat on the bed, struggling to breathe. “Do you want something? A glass of water?” I asked, but she ignored me. After a deep breath, she lay back down.

“Do you want something?” I asked again, but there was no response. Perhaps she was deaf. I gently touched her arm, startling her. She opened her eyes, fear evident in her gaze.

“Sorry, I’m very sorry,” I apologized, realizing I must have frightened her.

She looked at me, now calmer, then closed her eyes, once again ignoring my presence.

I left the room quietly and decided to write her a note. As I passed through the garden towards Grandpa’s desk, Daniela, absorbed in watching a beetle, asked if I had seen the woman again.

“Yes, she’s deaf. That’s why she gets scared and doesn’t respond,” I explained.

Paloma joined us. “You’ve seen the lady in the rented room again?”

“He says she can’t hear,” Daniela relayed. “But she’s not there.”

“She is there! She just can’t hear. She’s deaf,” I insisted.

“Who’s deaf?” my aunt asked, joining the conversation.

“The lady in the rented room near the courtyard,” I replied.

“Grandma doesn’t rent anything, and that old room is now your grandfather’s storage,” my aunt clarified.

“But I just saw her. She had a coughing fit,” I protested.

“What! Someone must have snuck in,” my aunt speculated, striding towards the room. We followed.

Upon arrival, my aunt flung open the door, peered inside, and turned to us with a dry remark, “Very funny,” before leaving.

I stood in the doorway, surveying the room filled with dust-covered boxes. The brass-cornered bed was now propped against the wall, its frame rusted and bare.

“I swear someone was sleeping here. The bed was made,” I insisted, looking to Paloma for confirmation.

“It’s all as it was before she came,” Paloma said, her face pale with apprehension.

“Daniela, did you see the lady?” my aunt asked.

“Yes, I saw her, but she wasn’t here,” Daniela replied.

Our aunt, visibly unsettled, turned to us, “Describe her.”

“She was older than Grandma, with white hair,” Paloma described.

“And she had a cough,” I added.

“And she wasn’t here,” Daniela reiterated, her words casting a chilling realization upon us.

Our aunt, paler still, revealed, “The last person to sleep here was Aunt Carlota, your grandfather’s aunt. She died of bronchitis long before you were born.”

The Bottle

Several weeks later, we returned to our home in Valparaíso. Though the adults never spoke of the slap or, as we called it, “Aunt Carlota’s ghost,” the topic was the highlight of the summer among my sisters and me. I must explain that my father was an atheist and my mother an agnostic. In those years, Chile’s entirely secular public education meant we never encountered the idea of invisible beings playing a part in people’s lives. In Chilean popular culture, ghosts were always meant to scare people, but we all remembered well that it was the lady who was afraid of us, not the other way around. This led to many discussions and theories.

As someone who had only read Oscar Wilde’s “The Canterville Ghost” and not yet discovered “The Sinister Dr. Mortis” comics, I never thought to be afraid. Paloma, on the other hand, got goosebumps remembering her encounter with a ghost, while Daniela, much younger and more pragmatic, occasionally reminded us that the woman wasn’t really there, so why bother about it.

Time passed, and Aunt Carlota’s ghost ceased to be our main topic of conversation, but there were things I couldn’t make sense of. Why was the ghost afraid of us? In all my readings about ghosts, I had never come across any that were afraid of the living. What made perfect sense, however, was the concept of Science Fiction. A time travel theory answered all our questions. If we had somehow traveled back to that room about 15 years earlier, everything made sense, including why the lady in the room was scared of us.

The time travel theory comforted me until one day, one of my mother’s sisters left a Dr. Mortis magazine at our house, which I found and read. After finishing it, I was scared of ghosts. Very scared. Shortly after, we encountered the corner ghost.

It was a sunny December day, about an hour before lunchtime, when our mother realized she was out of milk. This was a time before shopping malls and supermarkets. Shopping was done at neighborhood stores, and in Chile, or at least in my family, it was the children’s responsibility to do the daily shopping like milk and bread or emergency purchases.

“Paloma, Álvaro!” I heard our mother call. I was in the garden, trying to figure out how ants always follow the same path, but my scientific investigation wasn’t getting anywhere, so I answered,

“What?!”

My mother, who had the ability to move silently, replied right next to me, startling me so much that I jumped.

“When I call you, you’re supposed to come. You know perfectly well I’m not going to shout conversations at you.”

From inside the house, I heard Paloma shout,

“What?!”

My mother, with a resigned gesture, told me,

“Come inside. You need to go buy milk; I’ve run out.”

“No, not right now,” my sister protested upon hearing this, though she didn’t seem to be doing anything important. “Let Álvaro go, please.” Paloma often had a way with words, and more than once my mother had given in, but this time she didn’t budge.

“You both are going, and right now,” she said. “Paloma, here’s the money. It’s just enough, so don’t expect any change. Álvaro, take the bottle,” she said, looking at me. At least in those times, which were less stupid and consumerist: when buying milk or drinks, you had to bring an empty bottle of the same product, or they would charge you for the bottle. In this way, you only paid for the product.

We left the house and walked towards the small neighborhood store that sold bottled milk. It was hot, and neither Paloma nor I wanted to go to the store, but our mother was not in the mood to deal with back-talking children. She was rarely in a bad mood, but when she was, we all knew it was a very bad idea to argue.

As we neared the corner, I started to feel the heat. Having been playing in the garden, I was all sweaty, and the bottle was slipping from my grip. Afraid of dropping it, I asked Paloma if she could hold it for a moment so I could dry my hands on my pants. She agreed, but as luck would have it, just as I handed it to her, I tripped on a crack in the sidewalk. We both tried to catch the bottle, which flew up a bit before starting to fall right in front of us. We both gasped in fright and stretched our hands out at the same time, trying to catch it. We stopped when we saw that the bottle wasn’t falling at a normal speed, but very, very slowly. We looked at each other and withdrew our hands from that thing which had suddenly become anything but a normal bottle.

It descended through the air as if lighter than a birthday balloon, landing slightly askew, touching the ground with a softness that made a faint sound, like a spoon gently tapping against a glass. At that moment, I thought it was all just an optical illusion and expected the bottle to shatter into pieces. But no, it gently laid itself down on the ground, and only when it was fully resting on its side on the sidewalk, did it begin to roll at a normal speed, coming to a stop a little further away. Paloma and I didn’t move. We just stared at the bottle, half-expecting it to do something more, but nothing happened. Just a bottle lying on the sidewalk. I approached cautiously and nudged it with my foot, ensuring it wasn’t still under some strange spell of how a bottle should behave under gravity. It rolled a bit and then stopped.

Our eyes met, a silent agreement passing between us that what we had just witnessed was far from ordinary. In that moment, the ordinary world we knew had tilted, revealing a hidden layer where the impossible seemed to play by its own rules. We picked up the bottle, now just an ordinary vessel again, and continued on our errand, but our minds were elsewhere, pondering the mysteries of the universe that had just brushed against our reality.

“Let’s get out of here,” Paloma said, a tinge of fear in her voice, shattering the mental story I had been weaving where I was suddenly a boy with mental powers capable of moving objects with my mind. If this had happened decades later to another child, they would already be in line to become a Jedi apprentice. I picked up the bottle with a hint of reverence, but it remained just an empty milk bottle.

“What’s wrong?” I asked Paloma when I noticed she was indifferent to the bottle and kept looking around.

“It must have been a ghost that did that,” she said as we walked away from the spot.

“Do you think so? If that’s the case, it was a friendly ghost. If it had broken, we… would have been in big trouble.”

“I don’t care,” she replied. “A ghost is a ghost, and you and I know they exist.”

I remembered the woman in the room and the Dr. Mortis magazine. On our way back, and for weeks afterward, we avoided that spot, always crossing to the other side of the street. We told our friends from Villa Berlín, our neighborhood, about what had happened, and the place was dubbed “Ghost Corner.” The location commanded a certain respect from all of us. The last time I was there as an adult, I remembered the ghost.

Or was it that we really had mental powers?

Math class

The summer holidays passed with that bad habit they had when I was a child, always rushing by, and I started school again. As you might imagine, the days and hours flowed much slower than their summertime twins. I thought everything would be exactly the same as always: extremely boring with constant conflicts with teachers and therefore with my father. Everything had started years earlier when I began school eager to learn everything. My first disappointment was in the reading class at six years old. I was thrilled and eager to show the teacher that I already knew how to read. My grandmother had taught me at four years old, and by that age, I was already reading adult novels and thought the teacher would be delighted. When it was my turn to read, I started with “Pepa loves Mom and Mom loves Pipo,” but I hadn’t gotten far when my classmates complained to the teacher that they couldn’t keep up with me. The teacher asked me to stop and gave the turn to another child. He never asked me to read again. What I felt, and this was not the only time, was that I was being punished for doing things well. I had long suspected that adults had a very limited view of reality or were a bit foolish, and this confirmed it even more. Although the reading class from then on was the worst of the worst, the math class saved the situation as they taught me to add and subtract, and I found it fascinating.

The situation changed quite a bit the following term when, as a big deal, the teacher taught us to add two-digit numbers! I understood it in the first class, but I had to spend almost three months doing sums. I didn’t understand that at all. I looked out the window and saw a fascinating world with all kinds of mysteries and things to discover, yet I was locked inside adding two-digit numbers. Honestly, the adults were either crazy or all fools, but the final straw came in the last term when we were going to learn to add three-digit numbers! That was too much; I wasn’t willing to waste my time like that, and that very day I decided never again to listen to the teacher or my father, who seemed to think that everything the teachers said had to be done. I could understand him a little more. After all, he was a university professor of mathematics and physics, and everyone knows that people in the same profession always cover each other’s backs. So, from that moment on, no more doing homework. You can’t imagine the trouble I got into. Arguments with my teacher, arguments with the school principal, arguments with my father and the principal at the same time, and terrible arguments at home. It was the 60s, and physical punishment was expected from any good parent if the children didn’t fulfill their responsibilities. It was very unpleasant, but I was a stubborn kid who would never allow adults who thought that adding three digit numbers was something important to tell me what to do. Not many years ago, the topic came up during a meal at my father’s house, and he told us that neither he nor any of the teachers I had ever met a child as rebellious as me. If someone had bothered to explain to me what a curriculum was and why things were done that way, it might have been different. But they were too accustomed to giving orders without any explanation and expecting children to obey.

In the end, I won. My father literally got physically tired of hitting me with the belt and left me alone. With the math teacher, it was more subtle, but very surprising for me. We had reached a tactical agreement where I wouldn’t do homework, but I had to pay attention in class. One day, he was writing on the blackboard the sums that my classmates had to do at home, when something happened that was not only insulting to me but beyond that. He put up a sum we had already done three weeks ago. I, who as a general rule never participated in class, couldn’t resist and raised my hand. Everyone in class stopped writing when they saw me do that, and the silence caught the teacher’s attention, and he turned around.

“What is it, Álvaro?”

“That sum. The fourth one in the first row. We did it three weeks ago,” I said, all offended despite the fact that I, of course, hadn’t done it. He looked at me for a few seconds and then turned to my classmate Oscar, who was the best in mathematics.

“Oscar, can you check the homework from three weeks ago?”

Oscar, who was very organized, began flipping pages from left to right. Suddenly he stopped and concentrated on a page.

“Yes, Mr. Espinoza. It’s here.” Upon hearing that, the class exploded.

“That’s not fair!” someone shouted from the back.

“I struggle enough as it is; I don’t want to do the same thing again,” said another amid murmurs of similar comments.

“Alright, alright. Don’t worry. This is easily fixed,” Mr. Espinoza said and erased the first number of the series and put another one. He turned to me.

“No. We haven’t done that one,” I said.

To me, aside from feeling my intelligence insulted, it didn’t seem like such a big deal, but from that moment on, Mr. Espinoza, a teacher who had been awarded several times by the Valparaíso Ministry of Education as the best primary school teacher in the region, treated me with respect and never again asked me to do any math homework. From that moment on, all classes with him became enjoyable.

But, my father, not happy with the school results, transferred me to another one, and it was back to square one. When, after a few months, the teachers gave up and left me alone, something happened that I didn’t learn about because I was in my head, in worlds much more entertaining than those classes. They taught multiplication tables, and when the whole class knew them well, they moved on to divisions. Here we return to the year I met Aunt Carlota and the corner ghost. One day, I decided to listen to the math teacher, as he was new, and it turns out he was talking about dividing numbers of at least four digits. I found it very interesting until I discovered that you needed to know the multiplication tables, which until then had seemed to me an illogical way of adding and a waste of time. I started frantically learning them but had only reached the four table when one day the teacher did something he always did, but this time it was my turn. A surprise test. He called me to do a three-number division on the blackboard in front of the whole class. It was supposed to be easy, but I didn’t know what to do. I couldn’t explain that I didn’t know the multiplication tables and therefore couldn’t divide. He was a new teacher, and I was starting to get tired of always having all the teachers against me. I decided to bluff to the last moment, so I stood up and faced the division written in large chalk numbers in front of me. Four hundred sixty-two divided by three. I looked at the numbers for a long time and decided to tell him the truth.

“One,” said a voice. I looked at the teacher, thinking he had spoken, but he was looking at me with a bored expression. I turned towards the class. Everyone was watching me intently, but it couldn’t be any of them, because if I could hear the voice, so could the teacher, and he would not have allowed it.

“Put a one above the four,” the voice said. No, it hadn’t been anyone in the class, and the teacher hadn’t uttered a word. I turned back to the blackboard and placed a number one above the four, then looked at the teacher again. He still wore the same bored expression.

“Now a three under the four,” I did as instructed and glanced back at the teacher. He seemed somewhat more interested now.

“Put a one under the three,” the voice was in my head. Could it be a ghost that liked mathematics?

“Now put a six next to that one,” the voice directed. I complied and glanced back at the teacher. He smiled and nodded slightly. The voice was doing well. Was it a ghost, or could I read the minds of some of the brainiacs in class?

“Put a five next to the top one,” I did.

“Good. Now write fifteen under the sixteen,” I followed the instruction, and out of the corner of my eye, I saw the teacher still engaged. I decided to trust the voice in my head, despite not knowing who it was, but it seemed to want to help me.

“Put a one under the lower five,” I obeyed without hesitation.

“Now put a two next to it,” I wrote, growing more confident that the boy or girl with mental powers, or the ghost, knew what they were doing, and it was no joke.

“Put a four next to the upper five,” I did.

“Now, a twelve under the other twelve, and then a zero under the two in the twelve.”

I executed the steps and waited for further instructions, but the mysterious voice fell silent.

“Very well, Álvaro. You may sit down,” the teacher said. “Next time, remember to put the bars to separate the subtractions.” I looked at what I had written and then back at him, not understanding what he was talking about, so I quickly left the chalk and returned to my seat.

My desk was at the very back, trying to keep as far away from the teachers as possible, so I took the opportunity to look at all my classmates as I walked, in case someone made a gesture of “well done” or something that would tell me who the person with mental powers was. But nobody did anything. When I reached my seat, I decided it had been a ghost. Apparently, they were much nicer than what they put in horror magazines.

To this day, I still wonder who, or what, it was that helped me.

Someone in the wardrobe

The notion of something lurking in the closet appears in numerous books and movies, and I suspect many people feel a connection to this idea, as at some point, especially in childhood, they sensed a presence watching them from a slightly ajar door, where only clothes should have been. What I’m about to share concerns that very notion, albeit from the perspective of someone who doesn’t believe in ghosts.

My wife, my first child, who was about three years old, and I lived in an old apartment in the heart of Bilbao. This place belonged to my wife’s family, and she had spent her childhood years there. Not just that, the room we prepared for our son was her former nursery. When we arrived in Spain, after several years of married life across different European cities, we had the opportunity to inhabit this house brimming with memories, furniture, photographs, and all manner of items belonging to my wife’s ancestors. To me, everything seemed utterly fascinating. I had left my birth country at the age of ten and never returned. Since then, I had moved houses about forty times, cities around twenty times, and countries six times. In all these relocations, I had never once lived in a house with items from my ancestors. So it seemed incredible that my son could sleep in the very bed where his mother had slept as a child.

One day, while cleaning the room, María, my wife, told me that a few days earlier, while alone in the room, she felt a presence in the closet. This might have remained just a strange experience, had it not been for her recollection that as a child, when this was her bedroom, she often felt the same presence, replete with negativity and fear. She would request that the closet door be shut, but sometimes it was left open, and she couldn’t sleep, let alone dare to approach and close it herself. The presence grew stronger as she neared, and fear overcame her. To me, who found everything about the house quaint, this only added to its charm. An old house with ancient furniture, a trove of memories, and ghosts in the closet. What more could one ask for?

As you might have gathered, in my family, we have an ability to sense “strange energies,” and María was aware of this. One night, as I was contemplating going to bed or read a book, María called out to me with a nervous voice:

“Álvaro, can you come here?” I knew she was helping our son get into his pajamas, so I went to the room. They were both sitting on the bed, waiting for me. My wife took our son’s hand and said to him:

“Tell Daddy what you just told me.”

“There’s someone bad in the closet,” he said, a note of worry in his voice.

María looked at me, fear evident in her eyes.

When I was putting away our child’s clothes, I had already sensed that presence and knew it was very subtle. Like when you approach a house with a quiet dog. You know it dislikes your presence and watches you, but that’s all. However, I was not going to let my son endure the same experience as my wife. I was filled with anger. In two strides, I was beside the closet and looked inside. I saw nothing unusual, but I did feel a life force brimming with negativity, not directed at anyone in particular. It just existed that way and was also very, very small. It reminded me of a few weeks old kitten with a very bad temper. But my anger was strong, and I knew that whatever it was, it was nothing more than energy. Life energy, yes, but energy nonetheless. I focused on my own life energy, usually felt in the center of the chest, and let it grow and grow until I felt I could barely contain it. I gave it a tight squeeze and released it all at once. In less than a second, it flooded the room and the entire house. Of the small “angry energy,” absolutely nothing remained. To give you an idea of the scale, the “energy” was like a sigh, and what I released, a hurricane.

“It’s done,” I said to my wife.

“Thank you,” she replied.

“It won’t ever come back,” I told her.

“Is the thing that lived there gone?” asked my son.

“Yes. Despite seeming mean, I think it lived there by mistake or had nowhere else to go.”

“Is that why it was angry?” he asked.

“Probably. But I told it that it couldn’t live in someone’s room, and it’s gone,” I answered, without explaining that I had actually expelled it by force, or really, completely obliterated it.

As I said this, I actually felt a pang of pity for that “grumpy kitten energy.” Why it was there, what it was, or who left it behind are questions that sometimes cross my mind. All this despite not believing in ghosts, but it remains an intriguing puzzle.

A final farewell

Nearly a year later, I had established my first company, and my wife was pregnant with our second child. Our office was a room in our house, providing specialized services for an IBM product to businesses in the Basque Country. Starting a business in Euskadi with hardly any contacts, and worse, not being part of the Basque Nationalist Party, was a constant uphill struggle. However, I had high technical skills and excellent global contacts in my favor.

That day, I was entangled in tax payment issues, with no money in the bank as I was midway through a project and clients paid in 90 days. Overwhelmed, I longed for someone to talk to, someone who would just listen.

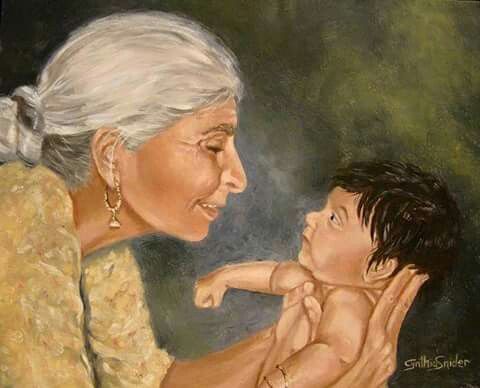

“What’s wrong, Alvaro?” a voice said behind me. I should have been startled, but the voice was familiar. I turned around. There stood my grandmother.

“Mamita… but…” I realized I wasn’t seeing her with my eyes; it was a mix of seeing the room/office and visualizing her in my mind. Astonishingly, she moved around the solid wood antique furniture, belonging to my wife’s family. When she touched a rocking chair, it moved. It didn’t seem like a hallucination.

She looked at me and said, “As a child, you were just like your mother, but now you’re increasingly resembling your grandfather.” I didn’t know what to say to someone I knew was thousands of miles away.

“I heard you and came to see you before I leave. What’s wrong?” she asked.

“Leave,” I thought. I knew it would be the last time I’d see my grandmother. I had to talk to her as much as I could.

“I have nothing but problems, and things seem to be getting worse. I feel everything is going wrong,” I replied, unsure if she could hear me. My grandmother surveyed the room, the computer, the furniture, and looked out the window. She gazed at the city, then turned to me.

“You live in a beautiful house, have a wonderful son, your wife loves you and will give you another child, and you say everything is going wrong?” she asked, then burst into hearty laughter. Smiling, she approached and gently touched my cheek, a sensation I undoubtedly felt. Then, she was simply gone. I was alone in the room, accompanied only by the computer’s hum and the city’s murmur outside the window. Less than an hour later, I stopped feeling my dear mamita’s life essence. My grandmother, a pillar of stability and affection, was no longer there.

That night, my sister called to tell me our grandmother had passed away that afternoon. I cried, but also felt grateful for having spoken to her. Not just that, she reminded me of life’s basic values. And for those who think I saw a ghost, which I don’t believe in, my grandmother died right after coming to see me and giving her best advice. That laughter taught me that at life’s end, all the jobs, successful businesses, fame, importance, or wealth fade compared to moments spent with loved ones. Each of these moments is a treasure beyond price, but they must be lived, experienced in the moment, aware of your children’s hugs, your partner’s kisses, nothing else existing in that small yet immense moment. Life is a sunset, walking barefoot on damp grass, the first snowflakes, your pet recognizing you, swallows in flight, or walking through an ancient forest. That all these are the real treasures, I understood with that laugh. It was clear my grandmother was a great teacher.

The End

My gratitude for all the support and first reading of the original Spanish version goes to Dolores Póliz for that editing which brings a touch of perfection to the story. Also, to Loreto Alonso-Alegre for her invaluable comments.

0 Comments